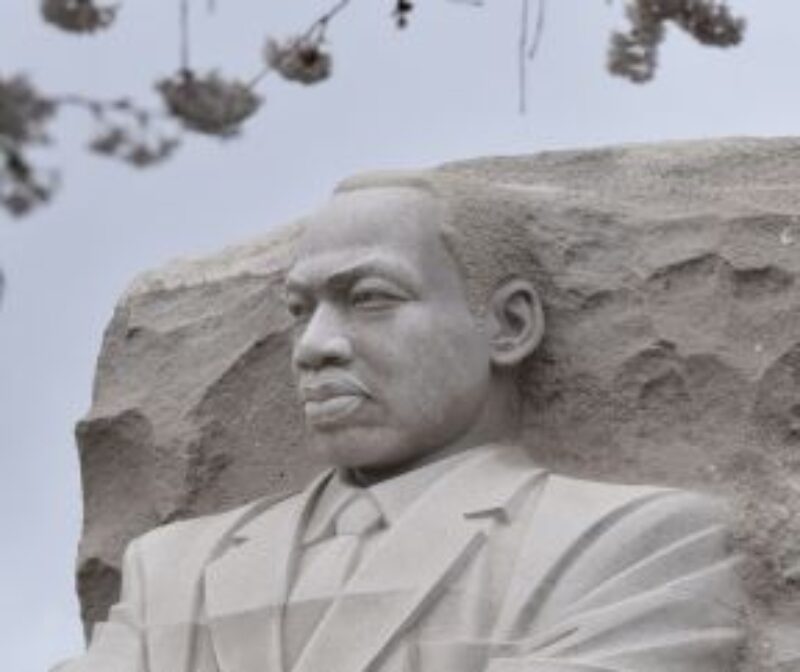

“As a teenager, I had never been able to accept the fact of having to go to the back of a bus or sit in the segregated section of a train. The first time I had been seated behind a curtain in a dining car, I felt as if the curtain had been dropped on my selfhood.”– Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story, New York: Harper, 1958)

Lessons from “Our Friend, Martin” and Dr. King’s journey

My earliest memory of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is learning about him in elementary school. Towards the end of the semester when all of our work was complete, I vividly remember the janitors wheeling in the TV that was connected to a VCR, and my teacher inserting a movie titled, Our Friend, Martin. All of us inner-city, urban, African-American students gathered on the carpet and watched the cartoon to learn more about the life of Dr. King and his assassination. One might think that’s pretty aggressive content for 2nd graders, but it was important for us to learn about our history and the current reality, sooner rather than later.

In the plot, Miles, a middle school student, and his best friend Randy take a class trip to King’s childhood home and discover a portal that transports them back in time to key moments in Dr. King’s life. The time-traveling adventure begins in King’s teenage years, where the two witness King’s academic excellence and dreams of equality. Later, they jump to key moments of the Civil Rights Movement, including the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the March on Washington. Along the way, they meet young Martin and interact with other historical figures, deepening their understanding of King’s vision for racial harmony.

The plot ends with Miles attempting to change history by warning Dr. King of his assassination. Miles learns that King’s sacrifice was crucial to advancing civil rights. Returning to the present, Miles and Randy find their community transformed, with King’s influence evident in the friendships and diversity around them.

As a doctoral student studying psychology and thinking about the lessons of this important film of my youth, I understand how key moments of King’s youth were pivotal in shaping him into the civil rights leader he became. His example highlights the developmental importance the moments gifted to us in our social and historical contexts. When Dr. King first questioned his “selfhood” in his teenage years, his experiences of discrimination, adversity and trauma had the potential to derail him. However, his life exemplifies how through processes of self-discovery, self-construction, and self-acceptance, King became and remained committed to pursuing justice and equality as he faced extreme hardships and resistance.

Youth today have the same developmental opportunities in key life moments. There will be times when their personhood will be questioned, and they will make decisions about who they want to be. Central to spiritual health and thriving is an authentic sense of identity, which clarifies one’s beliefs about oneself and relationship to the world. Although identity evolves over one’s life, youth must start the process of discovering an authentic identity in order to thrive, or they may remain in a “searching” cycle into their adulthood. As Dr. Thema Bryant articulates, “Individuals face myriad expectations and pressures to conform, often necessitating the suppression of their true feelings… Homecoming, the journey toward embracing one’s authentic self, liberates individuals from judgment and censorship, allowing them to express their genuine emotions” (Bryant, 2021, p.79). This autonomy fosters a sense of self-discovery and authenticity, enabling youth to navigate the complexities of identity formation with confidence and clarity (Spencer, 2024). It’s important to note that black youth often face stereotypes and expectations that hinder authentic identity development and they can lack the support, safety, and opportunities to explore their unique selves.

Authentic Identity through Self-Discovery, Self-Construction, and Self-Acceptance

In my dissertation project, I explore how self-discovery, self-construction, and self-acceptance contribute to authentic identity development, specifically in African-American youth. “In African American youth, disconnection from authenticity, or inauthentic identity development, can manifest in [identities] that are stereotypically perceived by others. It is through authenticity that Black youth develop an identity[ies] aligned with who they were created to be” (Spencer, 2024).

Through self-discovery, black youth can assess their past and connect the dots with their present reality. They are able to explore and reflect on experiences that have had an impact on their beliefs, moral constructs, and their reality. For instance, exploring biological, social, and spiritual facets of the past can give insight into the personhood of the individual. Black youth (or any young person for that matter) remembering the earliest years of their lives, as well as the history of their ethnic backgrounds, build foundations to explore where and what they may identify with.

Given the historical and systemic challenges faced by Black youth, the odds are heavily stacked against them in developing a healthy sense of authentic identity (Spencer, 2024). Monique Morris’s Black Stats: African Americans by the Number in the Twenty-First Century identifies the school-to-prison pipeline as a significant barrier, describing it as a system of policies and practices that criminalize students within educational environments. High-stakes testing, poor student-teacher relationships, racially biased dress code enforcement, and the lack of alternatives to exclusionary discipline contribute to punitive practices that disproportionately push Black youth out of schools (Morris, 2014). Thus, black youth may need more community support for identity formation.

Thinking back to the movie Our Friend Martin, one of my takeaways is the importance of accepting the past. In the movie, Miles tries to go back into the past to warn Dr. King about his assassination, trying to rewrite history. Later in the movie, Miles learns that changing history affects the present in the most unpredictable ways. In reality, we know that we cannot go back and change our past. However, many people live life trying to make up for their past experiences. Understanding and accepting the past is an important part of self-discovery.

Self-construction allows black youth to assess their discovered beliefs, how these beliefs were influenced by the world and contexts they grew up in, and how they make intentional choices on what beliefs, moral constructs, and values support who they are and want to become, rather than make choices as a defense mechanism or in reaction to the world as they construct their identities. Through self-acceptance, black youth come to embrace the beliefs, moral constructs and values that are the most congruent to themselves, so that they are able to prioritize authenticity.

As a child, I remember saying, “When I get older, I’m going to make sure I’m rich and that I’ll never struggle.” Through my teenage years and early adulthood, I did not become rich, and I did in fact struggle. The anxiety and depression that came from the sense of failure were pivotal; I had a “curtain drop” moment. I recognized a deep sense of trying to avoid my history in my present, and my history was dictating how l lived my life. Eventually, I decided to stop running from my past, and just be with myself in the present. My personal journey and process of self-acceptance ignited my passion to become a psychologist. I longed to aid people in beginning the process of authenticity. Authenticity is justice for the self.

Remembering the film Our Friend Martin is nostalgic, and more than that it is a reminder that discovering purpose is an ongoing process of discovering and accepting myself over and over again. Dr. King uncovered his purpose again and again as he was tested yet pursued justice and faith, in spite of circumstances.

Identity discovery through the life of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

In a recent With & For podcast interview with Drs. Pam King and Lerone Martin, Dr. Martin recounts the youth of Dr. King, and what led him to his role of becoming a civil rights activist. The young MLK was going to Connecticut during the summer to pick tobacco. Morehouse College, where King was a student, had a program for college students to earn money for tuition. King was just 15 years old, and this was his first experience outside of the South away from segregated stores and movie theaters. He went to a movie theater and sat in the front row for the first time. He went to a nice restaurant in Hartford and sat in the main dining room. He walked around Hartford, Connecticut, and didn’t see whites-only signs or colored-only signs. And he wrote how that experience, there in the Connecticut Valley, ignited his dream of a beloved community – about a world in which people were not stigmatized or limited simply because of the color of their skin. That summer is when he began to feel an urge within himself to serve humanity. He began the process of shifting from an identity of becoming a lawyer, who was going to work in the courts to tear down segregation, to understanding that he was going to be a minister and work on forming community through his faith (Lerone Martin, With & For Podcast, 2024).

Dr. King understood his context but did not succumb to its oppressive reality, and because he did not succumb to it, he was empowered to change it. When his selfhood was brought into question, he made the decision to pursue justice, and this decision made a lasting impact on generations to come.

Takeaways for those working with black youth

Black youth need support in the discovery of authenticity. Although specific life experiences may deter youth from hearing and responding to a calling on their lives, those same experiences have the potential to form young people toward their most authentic identities. In my faith tradition, I believe that God has a beautiful plan for restoration. Liberation psychologies often emphasize the importance of wholeness and authenticity. Martín-Baró states that liberation psychology seeks to go beyond breaking chains to building resources of compassion, justice, voice, and authenticity by acknowledging and building on the links among mental health, human rights, and the fight against injustice (Martín-Baró, 1994, p. 196).

The following are some ideas of how people can support youth development.

- Youth need space and independence from stereotypes and cultural and family expectations in order to test themselves and explore who they are and who they want to become.

Interestingly, most of MLK’s discoveries and ambitions came from places of solitude as he reflected on his early experiences. He formed his vision and discovered a sense of calling by seeking God and reflecting.

- Adults can design environments that are safe and supportive of creativity, self-expression, and reflection as a means for self-discovery, self-construction, and self-acceptance.

Dr. King often used a poetic narrative approach to persuade his audience that justice was achievable through both love and resistance. His use of creative language is why we remember the very words of his “I Have a Dream” speech. Building environments that support creative self-expression can give permission for the development of vision and calling. Black youth need environments where leaders resist the urge to silence or correct when black youth express themselves without permission.

- Adults must notice the passions of individuals and water the flowers of those passions. This takes time and curiosity on the part of adults and mentors but noticing and naming a young person’s passions can aid the development of a deep sense of who they are.

In seminary, Dr. King was under the mentorship of Morehouse College President Benjamin E. Mays, who had a huge impact on his spiritual development. Dr. King’s wife, Coretta Scott King, stated that Mays was a champion for racial equality who encouraged Dr. King to make Christianity the basis of racial justice (Scott King, 1969). Mays watered King’s flowers.

In my own journey I have come to understand that justice for others begins with justice for the self. Self-discovery, self-construction, and self-acceptance are vital for justice for the self. I understand that supporting and honoring authenticity and transformation at earlier stages of development is invaluable. Authenticity is contagious. If youth can be authentic within themselves, they can aid others in becoming authentic, consequently aiding in the development of a flourishing world. That’s the dream I have for my work and for others.

References:

Bryant, T. (2021). Homecoming: Overcome fear and trauma to reclaim your whole, authentic self. TarcherPerigee.

King, M. L. Jr. (1958). Stride toward freedom: The Montgomery story. Harper.

Martin, L. (2024). Interview on the With & For Podcast. Discussion on Martin Luther King Jr.’s transformative experiences and vision of a “beloved community.”

Martín-Baró, I. (1994). Writings for a liberation psychology. Harvard University Press.

Morris, Monique W. (2014). Black Stats: African Americans by the Numbers in the Twenty-first Century. The New Press.

Scott King, C. (1969). My life with Martin Luther King, Jr. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Spencer, A. (2024). Assessing Factors of Identity Development in African American Youth: Four Key Factors [Unpublished Dissertation or relevant source].

Continue Exploring

Practices

9 Principles of Effective Youth Service Organization

Research by the Thrive Center explores 9 principles that youth organizations can practice to effectively support and help youth thrive.

Blog

Being Part of the Village

Guest blogger, Dr. Anthony James reflects on his adolescence and the importance of community in helping youth thrive.

Youth

Empowering Youth to Thrive With, Through, and By Faith

Dr. Meredith Hope discusses the role of religion in youth thriving and ways caring adults can help enable spirituality in adolescence.