Part 1 of a two-part series. Link to Part 2 here.

Photo by: Dmitry Ratushny on Unsplash

“In psychology’s last fifteen years, a new vision of child and adolescent development has emerged. ‘Positive youth development,’ which provides a hopeful lens for caring for and empowering all children, promises hope for children facing even the greatest risks.”

-Pamela King

As the Church responds to the demand of serving and empowering children at risk in the United States and around the world, it is imperative not to draw upon theological and missiological resources, but psychological ones as well. Emerging perspectives on children at risk are to be lauded for holistic views, recognizing that children who have experienced severe neglect, abuse, and/or trauma have acute spiritual, physical, and psychological needs. Current theory and research within the social sciences offer a hopeful lens through which to better understand how the Church can respond in an effective manner to the young boy who has been orphaned by the ravages of war or the young girl who has offered her body as a source of profit and survival in the sex trade.

Positive Youth Development

A new perspective has evolved: positive youth development (PYD)—a vision theoretically linked to developmental systems models of human development that emphasize the potential for promoting positive change throughout life and considering the whole person within the systems in which their life is embedded.[1] Scholars who have begun to elaborate the positive development model[2],[3],[4],[5] insist that all youth have the potential for positive development, and that this potential means that young people may be regarded as resources to be developed, and not as problems to be managed.[6]

A developmental systems approach makes two important contributions to understanding how to serve and empower children at risk. First, this perspective emphasizes that all children have the potential for growth and change, providing the opportunity to focus optimistically, but not naively, on opportunities for positive development rather than pathology and problems. Secondly, such approaches understand that the potential for changed stems from the interactions between the individual and the environments in which they live. A systems approach takes an ecological perspective focusing on the relations between the child and the contexts in which they are embedded. Such systems might include their family (or lack thereof), peer group, community, economic, political, or religious systems. Instead of limiting one’s view of youth to preventing or fixing their problems, this new paradigm emphasizes the strengths, competencies, and contributions that young people can make, emphasizing ways to align their strengths with appropriate resources and support within their environment to maximize healthy development.

Although children at risk often experience what psychologists identify as the most severe risk factors (e.g., lack of family support, violence, sexual abuse, lower socioeconomic status, and poor nutrition) a developmental systems approach gives hope for the future of these children by emphasizing opportunities for growth and positive change. This perspective focuses on the need for healing wounds as well as growth and eventual thriving.

One of the significant contributions of positive youth development is that it promotes an optimistic view of young people. This approach aims to not only minimize risk and suffering among children, but intentionally nurtures strengths, competencies, and potentials that eventually enable them to make important contributions to their world.[4] A thriving young person is one that makes the most out of their personal and environmental circumstances. They experience personal satisfaction and meaning while contributing to their society. Such an understanding of thriving provides room for much variation-for example, a thriving young person in Pasadena, California, might look very different from a thriving young person in Malawi with HIV/AIDS. However, both can thrive. Thriving is based on an ability to positively adapt to circumstances in a way that promotes personal and social well-being. For example, thriving youth are often described as being hopeful about the future. In addition, thriving youth have positive values, are resourceful, have a sense of faith, and work at fulfilling their own potential. In addition, they find a constructive way to give back to others-whether that be their family, school, or community.

The second point of developmental systems approaches emphasizes the significance of the interactions between an individual and the many contexts in which he or she lives. From a systems perspective this is a dynamic relationship where the individual influences environment, just as the environment impacts the individual. These are “bi-directional” influences. For example, a local economic decline may affect the economic well-being of a family, which in turn causes a child to prematurely enter the workforce. In this example, the surrounding economic system impacts the child by causing him or her to enter the labor market. On the other hand, a particularly resourceful young person might rise in leadership in a gang because of his or her leadership skills. Here the individual qualities of the person impact the gang “system.” When these “bi-directional” interactions between the youth and the context are positive-to the benefit of both the individual and the system-then the young person is said to be thriving.

Most children at risk exist in severely difficult environments with little chance of thriving without direct intervention. Such children are often too powerless, too broken, or without adequate vision to understand how to identify or motivate the resources within their environments to put them on a path to a hopeful future. In many cases, their environments are so depleted that without intervention from relief workers and caregivers, such resources are not available to promote thriving in young people.

The 40 Developmental Assets

Positive youth development identifies resources that are associated with healthy outcomes and intervention strategies that are focused on strengthening the ecological infrastructure supporting youth within their community.[7] Search Institute provides a helpful framework to help identify what particular resources may be accessed to promote thriving in children at risk. Search Institute has identified 40 Developmental Assets that serve as the building blocks to healthy child and adolescent development. Previous research conducted by Search Institute has demonstrated that the presence of these assets are positively related to indicators of thriving[8] and negatively related to the presence of dangerous and problem behaviors in youth.[2] Developmental assets may be internal to a young person (e.g., positive identity, personal values) or may be external and embedded within the community (e.g., a caring adult, boundaries). Based on hundreds of thousands of North American youth, Search Institute’s research suggests that when it comes to such assets, “more is more.” The more assets a child reports, the more likely their chances of thriving and reducing risk and problem behaviors in their lives. Although most of their data is based on U.S. children and adolescents, the 40 developmental assets provide a helpful framework for those serving children at risk.

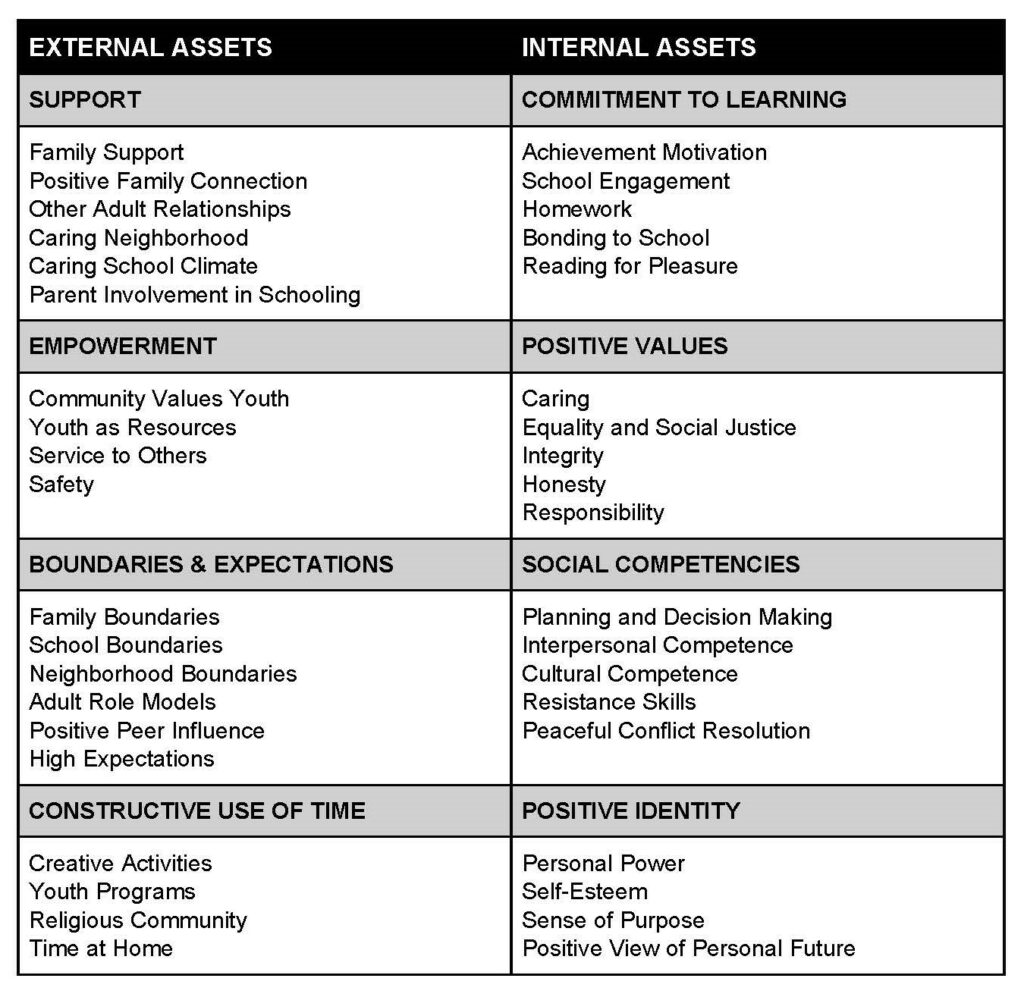

The 40 assets are broken down into 8 categories. Four categories are considered external to the child: support, empowerment, boundaries and expectations, and constructive use of time. These are resources that a child or adolescent might have access to through family, school, neighborhood, employment, or other activities. The 4 internal categories of assets include commitment to learning, positive values, social competencies, and positive identity. They include personal attributes, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors that promote healthy development. Healthy developmental outcomes are more common when there is an integration of social and personal resources.[5] Positive youth development emphasizes the importance of promoting a broad-scale developmental infrastructure where deficits in one area may be compensated for by assets in another area (see table).

Although at first glance this list of assets may seem irrelevant to the children we are addressing in this issue, many of these assets are crucial to effective intervention and care delivery for children at risk globally. Although such resources may be implemented differently for street children in Mumbai, India than for youth in a suburban after-school arts program, they provide important insight into how to intervene and care for children at risk. For example, when serving girls involved in the sex trade, the asset framework suggests that adult support outside the family is important to the healthy development of young people.[9] Given that girls involved in such work have been mistreated by adults due to the nature of their work, a youth worker serving such girls would need to pay special attention to the need for positive adults in the lives of these girls. In addition, these relationships would most likely need to be same-sex relationships and nurtured very carefully in order to engender trust with an adult outside the family. The assets indicate that a positive identity including a sense of personal power and sense of future are important. Young women who have been sexually abused are often suffering in these areas. Adults serving these girls might give special attention to creating opportunities for them to build a positive sense of identity and personal empowerment.

The assets also provide a helpful perspective in dealing with youth involved with gangs. Again, taking into consideration the role of adults outside the family, it is important to consider who might be the adults most often found in the lives of youth involved with gangs. They are often older members of the gangs. The asset framework suggests that effective adults need to be positive influences-not just any adult will do to promote positive development. An adult who is supportive and who promotes rules and positive expectations will promote thriving in young people. Often gang members, especially gang leaders, have many personal resources, such as leadership, resourcefulness, and motivation. However, these strengths are often misused and manifested in deleterious activities. The asset framework provides a helpful perspective to those working with such youth, emphasizing the need for having positive values such as integrity, honesty, caring, and restraint. Encouraging the ability to resist dangerous activities and promoting a sense of character and noble purpose in a young person may be important qualities to nurture in gang-involved youth.

How the church can respond

Positive youth development is a quickly growing movement in both academic and applied circles. Practitioners were the first to realize that focusing on youths’ problems was not an adequate approach to encouraging young people who were capable of contributing to society. Although efforts to reduce violence, teen pregnancy, and delinquency have indeed decreased those issues in youth, such an emphasis has not promoted contribution to society. In the words of Karen Pittman, “problem-free is not fully prepared.”[10] Scholars and even policymakers have caught on: focusing on problems is not an adequate means of serving our young.

For the Church to effectively serve and empower children at risk globally, the Church needs to view them as young people capable of thriving. This perspective does not minimize the trauma and abuse that they face daily; however, it challenges the Church to look beyond their brokenness towards healing and growth. It calls the Church to ensure that these children do not merely survive, but that they thrive and become all that God intends.

Editor’s note

This article was originally published in Theology, News, and Notes, Vol. 52, No. 03 at Fuller Theological Seminary.

Endnotes

[1] P. L. Benson, All Kids Are Our Kids: What Communities Must Do to Raise Caring and Responsible Children and Adolescents (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1997).

[2] P. L. Benson, N. Leffert, P. C. Scales, and D. A. Blyth, “Beyond the ‘Village’ Rhetoric: Creating Healthy Communities for Children and Adolescents,” Applied Developmental Science 2, no. 3 (1998): 138-59.

[3] R. F. Catalano, M. L. Berglund, J. A. M. Ryan, H. S. Lonczak, and J. D. Hawkins, Positive Youth Development in the United States: Research Findings on Evaluations of Youth Development Programs (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1999).

[4] W. Damon, “What ls Positive Youth Development?” The Annals of the American Academy 591, (2004): 13-24.

[5] J. S. Eccles, and J. A. Gootman, Community Programs to Promote Youth Development (Washington D.C.: National Academy Press, 2002).

[6] R. M. Lerner, Liberty: Thriving and Civic Engagement among America’s Youth (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2004).

[7] R. M. Lerner, J. V. Lerner, J. B. Almerigi, C. Theokas, E. Phelps, S. Gestsdottir, S. Naudeau, H. Jelicic, A. Alberts, L. Ma, L. M. Smith, D.L. Bobek, D. Richman-Raphael, I. Simpson, E. D. Christiansen, and A. von Eye, “Positive Youth Development, Participation in Community Youth Development Programs, and Community Contributions of Fifth-Grade Adolescents: Findings From the First Wave of the 4-H Study of Positive Youth Development,” Journal of Early Adolescence 25, no. 1 (2005): 17-71.

[8] P. Scales, P. Benson, N. Leffert, and D. A. Blyth, “The Contribution of Developmental Assets to the Prediction of Thriving among Adolescents,” Applied Developmental Science 4 (2000): 27-46.

[9] J. Roth, J. Brooks-Gunn, L. Murray, and W. Foster, “Promoting Healthy Adolescents: Synthesis of Youth Development Program Evaluations,” Journal of Research on Adolescence 8 (1998): 423-59.

[10] K. J. Pittman, M. Irby, and T. Ferber, “Unfinished Business: Further Reflections on a Decade of Promoting Youth Development,” in Youth Development: Issues, Challenges, and Directions (Philadelphia: Public/Private Ventures, 2001), 7-64.

Continue Exploring

Thriving

Survival of the Equipped (Part 2): Giving our Youth the Tools for a Thriving Life

Explore how youth programs can help teens strengthen the developmental assets that contribute to their thriving.

Youth

Kids and Community (Part 1): How to Find the Right One for Your Kids to Thrive

How do you find a community to support your family? What kinds of support help families grow spiritually healthy and thrive.

Youth

Kids and Community (Part 2): Adolescents and the Value of Loving Relationships that Display a Loving God

Why do kids need a community that models love, and what does emotional safety have to do with it. Part 2 of a 3-part series.