Embodiment is when we feel “a sense of positive connection or being at one with our body.”

H. McBride

Last month I discussed the importance of attuning to the body and offered a practice of telling the story of your body – past, present, and future. As we pay attention to our bodily needs, we become better at interpreting our emotional bodies. Our emotions are deeply linked to how we make meaning of our lives. They signal what is important to us. For example, if you find your body tense and your heart racing when your child brings home a less than perfect report card, attuning to your body might reveal a deep (and perhaps unfounded) fear for your child’s future. Our bodies provide us valuable information. If we are disconnected from our emotional bodies, we will often find ourselves acting in ways that separate us from our loved ones, causing disruption in our lives.

Many of us have experienced environments where we were told to sit still or to calm down or to take it like a man. Many of us can remember being told to act lady-like, but what that really meant was, smile and keep your thoughts to yourself. Growing up with these kinds of messages can disconnect us from the goodness of our bodies. The following is a practice that helps us reconnect to the goodness of being a body.

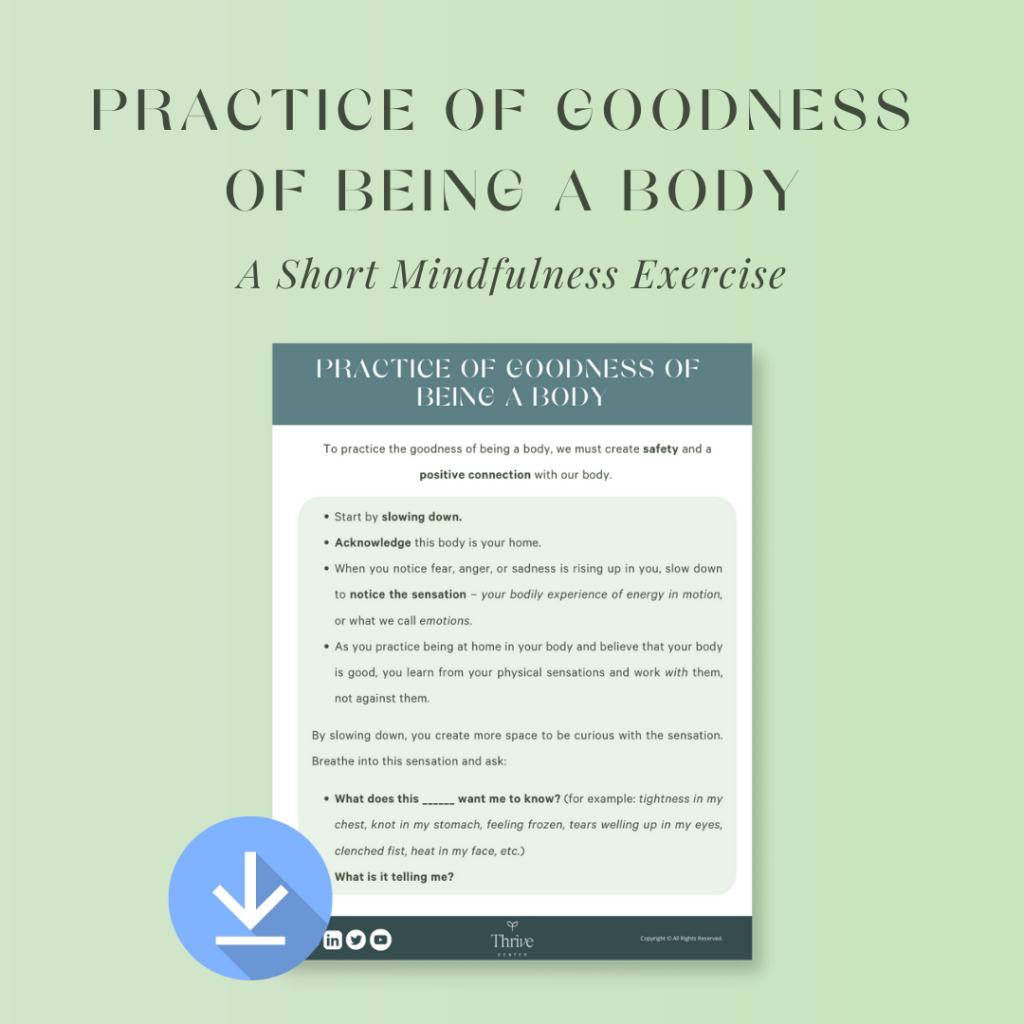

Practice the Goodness of Being a Body

Embodiment is essentially the way that we are, the story of how we show up, along with the story of who we have been up until this moment.

To practice the goodness of being a body, we must create safety and a positive connection with our body.

- Start by slowing down.

- Acknowledge this body is your home.

- When you notice fear, anger, or sadness is rising up in you, slow down to notice the sensation – your bodily experience of energy in motion, or what we call emotions.

- As you practice being at home in your body and believe that your body is good, you learn from your physical sensations and work with them, not against them.

By slowing down, you create more space to be curious with the sensation. Breathe into this sensation and ask:

- What does this ______ want me to know? (for example: tightness in my chest, knot in my stomach, feeling frozen, tears welling up in my eyes, clenched fist, heat in my face, etc.)

- What is it telling me?

There may be a real reminder of a time when you previously felt afraid in this situation, and your body is sensing you may be in danger again. Your body is doing its best to protect you; however, it’s possible that this time you’re not actually in danger. Regardless, the sensation of fear is real and is trying to pull all your attention to this fearful sensation with fear-filled thoughts. It wants you to do something about it! (Pollatos & Ferentzi, 2018).

To practice embodied living, invite this part of you that feels afraid to be with you, to come along. Imagine having compassion for this part of you; with kindness, acknowledge what it is sensing and how it is informing you. Allow it to be there instead of fighting or ignoring it (“I see you; I’m listening. What are you afraid of?”). As you listen to what your body is telling you, remind yourself it’s okay to be afraid. The wise part of you is capable of making a wise decision and can lead you forward in this moment. By zooming out from the fear, you create space for the fear to be there without letting it control your life. Fear doesn’t have to be shamed or punished – but it does not get to lead you or keep you from experiencing life with vitality and wholeness. This practice teaches your body that you are safe.

You can live from the wisdom of your body – and while that does not mean you escape the discomfort of your bodily sensations – you can make space for them in a loving way that creates acceptance for all of yourself to be present, and allows you to show up in the world as your genuine self, in the goodness of your body (Bowler, 2020; Doyle, 2023).

Pathways to Embodiment

Our embodiment is influenced by the communities we are a part of, the relationships and cultures that have shaped us, the contextual and social scripts we have been handed about who we are allowed to be, how we have been encouraged or discouraged to take up space, and the sense of freedom, safety, and agency we experience in the world.

The way that we embrace and practice the goodness of being a body directly impacts the way that we interact with and engage with other bodies. Embodiment can be understood and experienced as we develop pathways toward mental freedom, physical freedom, and social power (McBride, 2021; Piran, 2017).

Mental Freedom is our ability to challenge society’s ideas about our body, especially parts of ourselves that have nothing to do with our physical appearance. Mental freedom stands in contrast to self-silencing behaviors; rather, it is the ability to freely express our unique selves – including communicating our needs and our emotions. Mental freedom also involves challenging rigid gender stereotypes, and telling an authentic story with our embodiment.

- Consider a younger version of you, before you learned societal expectations and restrictions for how you should dress, or change your body, or express your thoughts and emotions.

- How might the six-year-old version of you freely express yourself?

- Has a part of you become silenced or hidden that actually carries wisdom and freedom for you to be authentically you in your body?

Physical Freedom is shaped by our social context and includes our sense of physical safety, respect, care, ability to rest, and engage in movement. Physical freedom involves accepting our physical body, our developmental changes, desires, and appetites with a sense of care, and without shame. Our physical freedom is intertwined with the freedom of others, highlighting the importance of communities that foster physical freedom and safety.

- Consider how your body signals to you what you like and do not like; how do you know?

- As you continue to develop throughout your lifespan, how would you like to be attended to when you feel sad? angry? excited? joyful? afraid?

- Imagine attending to yourself in the same way.

- Consider discussing this with your partner or close friend and learn how to be present to each other in ways that cultivate freedom and safety.

Social Power fosters embodiment by re-writing dominant cultural scripts and changing systems that have limited, restricted, and oppressed the bodies of those society has viewed as “other” (whether due to gender, race, ethnicity, ability, sexual orientation, weight, etc.). Those in positions of power and privilege must create spaces that include and value all bodies. In contrast to disempowerment that is often perpetuated through marginalization and reinforcing “body hierarchies,” social power cultivates safety without requiring suffering or physically altering one’s appearance to be viewed as acceptable. Social power can be built alongside others who validate and share similar experiences.

- Notice how you occupy space as you move about your day; pay attention to your posture and your physical sensations when sitting or standing near people who hold varying degrees of social power.

- How do you carry your body and how do you interact in these settings? What is said verbally and non-verbally in these settings about who holds social power or whose bodies are considered more important?

- What kind of body is not present nor considered in this space? How might you come alongside someone experiencing identity-based oppression, or how might you reach out to others for support?

When we treat our bodies with nurturing care, respect, and curiosity, rather than judgment, criticism, or shaming, we foster our physical and mental freedom. We can participate in social power that celebrates the beautiful diversity and complexity of being human, without perpetuating harm. By learning to connect with our whole self and dialogue with what’s happening inside of us, we are more able to move toward health as embodied individuals and as interconnected communities.

It is through our embodiment that we are alive and experience this world – as I discussed in Part 1, I experienced the dolphins in all of their glory. As embodied beings, we have the capacity for thinking, feeling, and sensing simultaneously. Our ability to identify feeling states and use language to capture what we sense in our bodies as it is processed in our minds is essential for decision-making and for effective communication with others.

When we repeatedly live disembodied lives that prioritize thinking and doing over being and connecting, we disengage from ourselves and the goodness of our body. Not only do we miss important information that our bodies offer, but we may miss out on forming a collective body and healing community with others. Try some of the practices offered in this series to connect more deeply with your body and the collective body in your journey toward spiritual health and thriving.

For more resources on Embodiment, see:

Bowler, K. (2020, June 15). Hillary McBride: Living inside our bodies [Audio podcast episode]. In Everything Happens with Kate Bowler. Duke University. Apple Podcasts. https://katebowler.com/podcasts/hillary-mcbride-living-inside-our-bodies/

Doyle, G. (2023, May 8). 206: How to follow the wisdom of your body with Dr. Hillary McBride [Audio podcast episode]. In We Can Do Hard Things with Glennon Doyle. Glennon Doyle & Cadence13. Apple Podcasts. https://momastery.com/blog/we-can-do-hard-things-ep-206/

Fogel, A. (2009). The psychophysiology of self-awareness: Rediscovering the lost art of body sense. W. W. Norton & Company.

Fogel, A. (2011). Embodied awareness: Neither implicit nor explicit, and not necessarily nonverbal. Child Development Perspectives, 5(3), 183-186.

Fogel, A. (2020). Three states of embodied self-awareness: The therapeutic vitality of restorative embodied self-awareness. International Body Psychotherapy Journal, 19(1).

McBride, H. L. P. (2021). The wisdom of your body: Finding healing, wholeness, and connection through embodied living. Brazos Press.

Payne, H., Koch, S., & Tantia, J. (Eds.). (2019). The Routledge international handbook of embodied perspectives in psychotherapy: approaches from dance movement and body psychotherapies. Routledge.

Piran, N. (2017). Journeys of embodiment at the intersection of body and culture: The developmental theory of embodiment. Academic Press.

Pollatos, O., & Ferentzi, E. (2018). Embodiment of emotion regulation. Embodiment in Psychotherapy: A Practitioner’s Guide, 43-55.

Verny, T. R. (2021). The embodied mind: Understanding the mysteries of cellular memory, consciousness, and our bodies. Pegasus Books.

Continue Exploring

Emotions

Want to become more present, healthy, and connected? Pay attention to your body (Part 1)

Thrive Fellow, Lauren Van Vranken, offers practices for reconnecting to our bodies and asks us to think about our relationship to our embodied selves.

Practices

Burnout Culture: Is it Possible to Rest and Achieve?

How do we address the problem of burnout in our modern society?

Emotions

Can We Become Happier?

There are scientifically-supported practices that help us get happier, so learn more about what to do and what not to do.